World War II and Montreat

The summary and links on this page are based on available resources. Direct links to those resources are listed at the bottom of the page. If you have source material or other relevant information to share, please email history@montreat.org.

Between October 1942 and April 1943, the US State Department contracted with the Mountain Retreat Association (MRA) to house two hundred sixty-four detainees in Assembly Inn as part of a State Department program to exchange German and Japanese diplomats, businesspeople, and their families for US expatriates held in Axis countries.[1] The “Special War Problems" division of the State Department detained German and Japanese citizens as well as some American citizens (the latter group primarily composed of children of the first two groups).

Background of Montreat's Role

Shortly following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States' entry into World War II, the Special War Problems Division (a part of the US State Department) detained individuals noted as Axis diplomats, Japanese and German nationals, and their families. These detainees were assigned "special status" and were designated for the exchange for US citizens being held in those countries.

Detainees were housed in various locations around the country. In some cases, families were separated, with men in one location and women and children in another. In Western North Carolina, detainees were housed initially at the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, but the State Department soon began looking for more affordable housing options. Montreat representatives met with state department officials and offered the Assembly Inn as an alternative.[2]

Two hundred sixty-four detainees were eventually relocated to Assembly Inn. The decision to detain these individuals in Montreat was not widely covered by the press at the time. Despite the lack of media coverage, the detention camp at Montreat was well known within the Presbyterian Church, according to one scholar, and opinions were sharply divided between support and criticism. [3][4][1]

An example of this is seen in letters written to Dr. Anderson. Fred Johnson, a resident of Knoxville, TN, encouraged the MRA to make Assembly Inn available to the government "in taking care of the Japanese and German families that are interned in this country...I would do it to help the Government in the greatest emergency that any living man has known to maintain our Christian civilization." Johnson later wrote, "I hope you will work out something with them and let the Assembly Inn be consecrated to this effort as it has it has been consecrated to every other good effort in the Christian civilization of America and the world since it was built."[3] Others had different views. Homer McMillan, executive secretary of the Executive Committee of Home Missions (PCUS), wrote "...I doubt if the Church will be very enthusiastic about having those Japs and Germans in our church property, when our own citizens who are being detained in Japan are finding it difficult to get along."[4]

Many have speculated about Dr. Anderson’s motivations for this arrangement. He published a letter in the Christian Observer where he outlined, among other things, his motives.[5]

"We consider it a privilege for Montreat to be of some service to our government in this critical times of its great need [sic]. It will also be an opportunity to show these people who have been providentially within our borders the meaning of the Christian life and they will receive at the hands of all who serve them an example of the Christian way of living. It will also give the Assembly Inn some financial help during the months it needs it most."[5]

The Detainees

There were one hundred thirty-eight individuals of Japanese heritage[5], primarily representing forty families who had been living in Hawaii during the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Most of these were women and children, families of men who had been detained indefinitely by the US Government and sent to other locations. While many of the women were Japanese nationals, many of the children were territorial citizens

who were born in the United States. UNC Chapel Hill professor and author Dr. Heidi Kim’s academic research noted some other possible reasons for the need for housing, suggesting that detention on the mainland seems to have been "at least partly the result of a plan to keep them away from Hawaii for a few months in order to render their knowledge outdated."

Kim noted that Japan also delayed the exchange for unknown reasons. The Japanese detainees at Montreat, she suggests, were told that "the delay was because of the unsafe conditions in Singapore, which was originally intended as their destination."[6: par. 4] Dr. Kim also noted that upon arrest, their property was confiscated and they were only allowed to bring a small amount of money.[6: par. 7]

Life at Assembly Inn

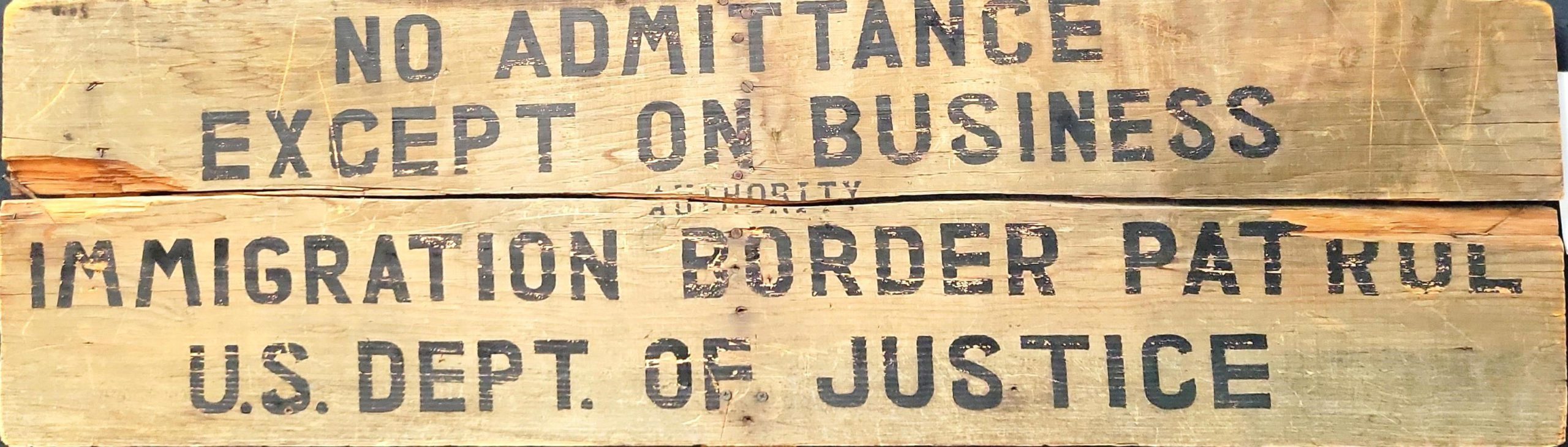

Detainees were held against their will and under guard. In later years, detainees recalled the conditions of incarceration in Montreat as less than luxurious in comparison to accommodations at the Grove Park Inn. Overall, however, accounts of their incarceration include descriptions of being comfortable and well-treated. "Despite some behind-the-scenes initial opposition, the courtesy and even friendliness that locals extended to the incarcerees appears to have been a memorable feature on both sides."[6: par. 12]

Detainees were housed on different floors based on nationality and were generally confined to Assembly Inn. "All the rugs, good furniture, and tablecloths were removed in preparation for the detention, and rope swings were constructed for the children. A parlor upstairs was designated as a schoolroom, half for Japanese and half for German children. Older Japanese American children instructed the younger ones. The inn's parking lots were used for outdoor games and exercises."[6: par. 8]

Many Japanese families did not have coats or other garments appropriate for the winter, so provisions were made for warmer clothing after a complaint was made to the State Department.[8] Healthcare was arranged through the government, and there is some evidence that German individuals were taken to Asheville for treatment.[6: par. 8] Reports suggest that the food was considered good (although the government took to having weekly inspections of the meals following an isolated instance of food poisoning).[9][10]

Some detainees’ requests were accepted while others were denied. A request for a woodworking space was approved, while a request to allow beer was denied.[11] Although there was a prohibition on religious programming, Assembly Inn rooms were supplied with Christian Bibles and other religious materials that had been translated into German and Japanese. Requests for Buddhist and other religious texts were denied by the State Department.[6: par. 13]

The End of Detainment and Its Legacy

In April of 1943, the Japanese and German detainees boarded a train in Black Mountain headed to internment camps in the Western United States. Recent studies have provided some context to what happened to these individuals after they left Montreat. In a submission to the 2020 National Conference on Undergraduate Research, Jacob McIntosh noted that "over time, they would be repatriated, sent back to where they were previously living, or became American citizens."[7: pg. 468] "The Japanese American and German families were transported in May 1943, along with one Japanese man, a German woman and her two children who had come from another site, to camps in Texas (Crystal City, Kennedy, and Seagoville), with most of them sent to Crystal City. Most sailed on September 2, 1943, to the neutral port of Goa, India, on the MS Gripsholm, along with several hundred other Japanese Americans and Latin Americans."[6: par. 16]

Heidi Kim chronicled the lives of Jane Asama and Tomo Tzumi during their time in Montreat and noted the long-term impact of this experience. "Temporary amenities could do little to ameliorate the pain of the incarceration as these families suffered a wracking uncertainty, separation, financial hardship, and the long-term effects of repatriation to a war-torn Japan."[6: par. 16]

The MRA was paid $75,000 for the use of the Inn.

The MRA’s decision to make Assembly Inn available for the detainee program has provoked varying opinion and debate and left a legacy of pain, anger, and defensiveness. For some, the detention in Montreat was a moral sin akin to the US Defense Department’s internment of Japanese Americans during the same period. For others, Montreat’s actions were morally justified by the shared goal of the three participating countries to ensure the safe custody and passage of its citizens and their children in a time of war. Regardless, indefinite detention was and remains a serious moral issue in the United States and other parts of the world, considered by many to be a violation of international law.

We deeply regret that the MRA’s actions have distanced people from Montreat, and in some instances, from the church itself. We pledge to make information about our history available to anyone who wishes to know more about these events and the context in which they occurred. A close examination informs both our current and future decisions in ways that are consistent with Montreat’s calling to provide Christian hospitality to all.

The summary above is taken from collected accounts and histories on hand. The references below provide full source material for the quotes and citations listed above. Further, the Presbyterian Heritage Center hosts an ongoing exhibit about the events of detainment in Montreat. We encourage you to visit its website and visit in person. Finally, if you have source material or other relevant information to share, please contact tannerp@montreat.org.

References and Sources

- ^Rev. Dr. Robert Campbell Anderson, “The Japanese and German Internees” in The Story of Montreat: From Its Beginning, 1887-1947, self-published, 1949, pg. 116-120.

- ^Briggs, M. E. Letter to Dr. Anderson. 15 November 1942. Presbyterian Heritage Center.

- ^Anderson, Dr. Letter to M. E. Briggs. 16 November 1942. Presbyterian Heritage Center.

- ^Anderson, Dr. Letter to M.E. Briggs. 18, November 1942. Presbyterian Heritage Center.

Other Resources

- Freeman, Trevor. (2005, June) "WNC History: The Story Behind Detainee Camps at Grove Park, Assembly Inn", Asheville Citizen Times. https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2022/06/05/story-behind-detainee-camps-grove-park-inn-montreat-assembly-inn/7473307001/.

- Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i (JCCH). (2008). "Lesson Three: Internees Stories". Japanese American Internment Unit for Modern History of Hawawi’i . https://www.hawaiiinternment.org/sites/default/files/Modern%20History%20of%20Hawaii_0.pdf.

- Presbyterian Heritage Society. (2022) Montreat History Spotlight. World War II: Detention of Diplomats, Businessmen and Families.

- Presbyterian Historical Society, edited by James H. Smylie (1996). Montreat: A Retreat for Renewal, 1947-1972, C. Grier Davis; American Presbyterians: Special Issue Commemorating the Centennial of the Montreat Conference Center.

- Other historical details are drawn from summaries of Mountain Retreat Association (Montreat Conference Center) meeting minutes and administrative papers housed at the Presbyterian Heritage Center, Montreat, NC.